The last time football stopped | Swansea Town’s story

While those of us who love Swansea City cannot wait for the day we can get back to the Liberty Stadium to cheer on Steve Cooper and his side, there is no escaping the fact these are unprecedented times. Not just for Wales and the rest of the United Kingdom, but the world as a whole.

In a few short weeks the ebb and flow of daily life has changed beyond recognition, including the indefinite postponement of all football until Government and healthcare authority guidance around the Coronavirus pandemic deems a return to action is possible.

The rare nature of the current situation is underlined by the fact this is the first time since the Second World War that football has been indefinitely suspended.

If you put that in context; the last stoppage of this nature was due to a global conflict that would claim the lives of an estimated 70 million to 85 million people.

As is the case now, events had a major impact all over the globe and in a far more crucial context than that of sport and football.

Nevertheless, it would prove to be an important period for Swansea Town – as the club was then known – and Swansea itself.

Here we take a look at some of the key events of the period on and off the pitch.

The appointment of Haydn Green, the emergence of young talent and the outbreak of war

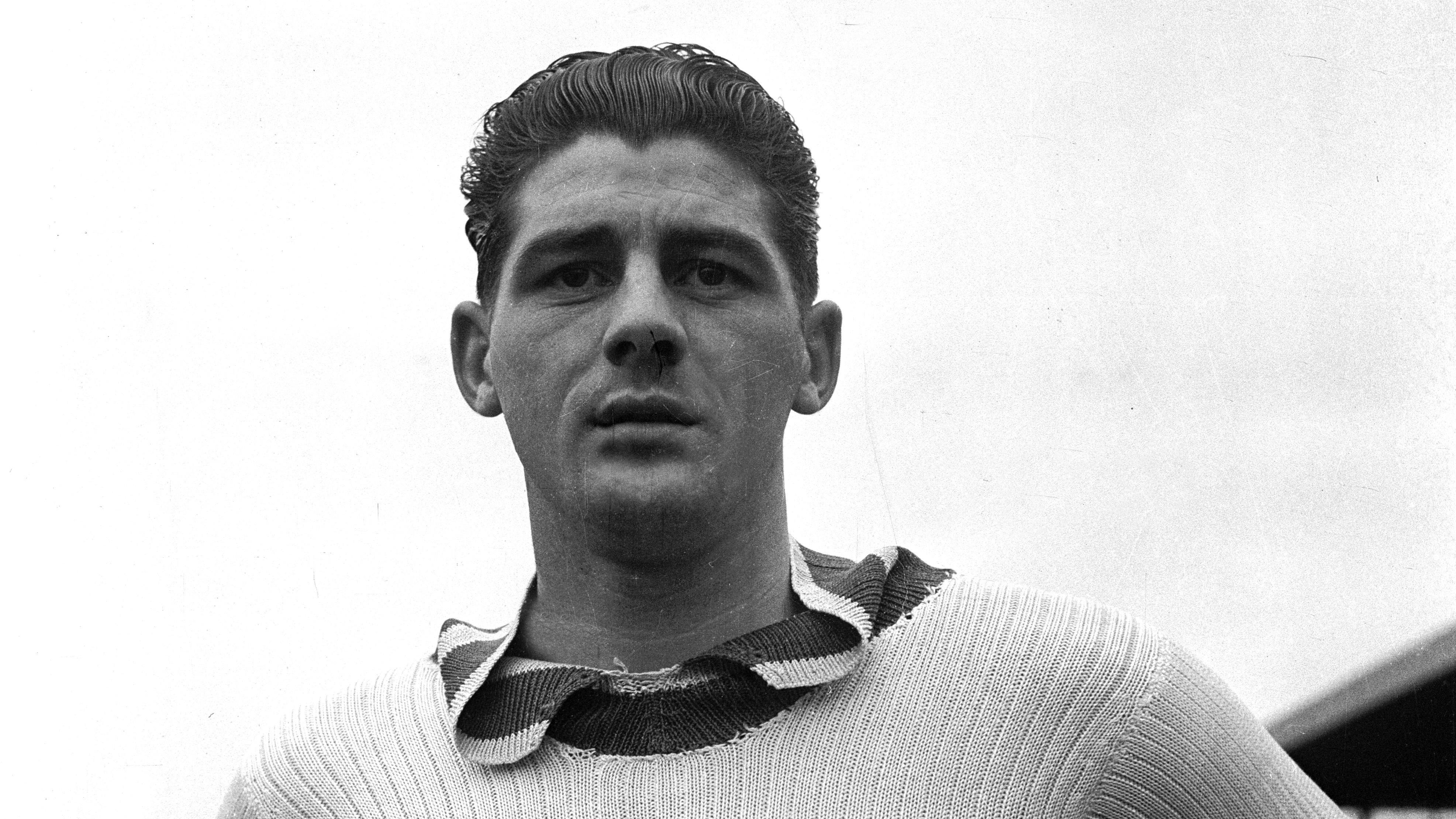

In the history of all Swansea managers, the one appointment where it is particularly tempting to wonder what might have been is that of Haydn Green.

The Englishman was appointed manager of Swansea Town following Neil Harris’ departure to Swindon Town in May of 1939.

Green, who had previously managed Lincoln City, Hull City and Guilford City, had a strong belief that Swansea Town could act as a football nursery.

His plan centered around nurturing and developing the wealth of young footballing talent from working class communities in the area, ensuring the club’s lack of relative financial muscle need not hinder its footballing prowess.

Green’s vision looked to be especially prescient as – around the same time as his appointment – there was a notable football success for the area’s fledgling footballers.

For many years, the Swansea Schools Football Association had acted as a conveyor belt for future Swansea Town stars.

In May 1939, just under four months before the outbreak of war in Britain, the Swansea Schoolboys won the English Schools Trophy for the first time following a 2-1 victory over Chesterfield in front of a 20,000 strong crowd at the Vetch.

Under the guidance of sports teacher, Dai Beynon, the Swansea Schools side would go on to win the trophy another three times - as well as the Welsh Trophy on seven occasions - between 1945 and 1955.

The declaration of war would sadly put the development of many of those players on the backburner, although there would be opportunities for some who were taken on as ground staff at the Vetch and given their chances in friendlies or junior football.

Green and Abe Freedman, who became Swansea chairman for the second time in his career following the death of Owen Evans prior to the 1939-40 season, signed the likes of Jackie Coulter, Billy Sneddon, Sam Briddon and Kitchener Fisher as senior figures to provide the squad with some experience amidst the planned youth policy.

Indeed, Fisher would go on to skipper the side during the war years, and play a key role in the rebuilding phase once conflict had concluded.

With others including Roy Paul, Bryn Allen and Frank Squires still in their teenage years, the Swans had heaps of potential – and a bright generation of youngsters surely on the way through - but were forced to wait six long years before playing a full league season as the sport came to a standstill.

The Swans’ 1939-40 campaign began with a home match against West Bromwich Albion, which proved historic in its own right as the fixture marked the first time shirt numbers were compulsorily worn on the back of jerseys.

The Swans fell to defeat against the Baggies but the Jack Army were not too disheartened as they found themselves pleased with the performances of the new signings and the match had acted as a diversion from the constant reminders of the possibility of the outbreak of war.

A victory away to Southampton and a heavy 8-1 loss against Newcastle United followed, with war being declared within two days of the loss at St James’ Park.

Football had continued throughout the First World War but that was not to be this case this time round, with conscription introduced and the English League programme being abandoned indefinitely.

Just over two weeks after the declaration of war, the Football Association declared the season null and void. Fans, staff and players braced themselves for the potentially perilous next chapter in the club’s history.

Moving to St Helen’s and a new league structure

In sporting terms, the main difference between then and now was that while official league football was suspended, supporters could still get their fill of football with the authorities deeming it an important boost to morale for the public and for those serving in the armed forces.

However, as the scale of the conflict grew, the Government would go on to impose a travel restrictions which meant the prospect of teams travelling long distances to fulfil fixtures was no longer available. Additionally, crowds were limited to 8,000 as a public safety measure, although both measures would later be relaxed to a certain degree.

The solution would be regionalised leagues, with Swansea falling into the South-West leagues, although the geographical reach of these divisions narrowed in lines with Government regulation.

Swansea travelled as far as Plymouth and Torquay for games during the 1939-40 season, but such journeys would soon be out of the question.

They were joined in these competitions by the likes of Cardiff City, Bath City, Lovells Athletic, Aberaman, Newport County and the two Bristol clubs, while there were also regionalised cup competitions. Numerous charity games and friendlies were played during the war years too.

However, the Swans ability to keep playing was hindered by the Vetch Field being commandeered for use as a base for anti-aircraft weaponry ahead of the 1940-41 season.

Fortunately, a solution would be found when an agreement was reached for the football club to play their games a little further down the road at St Helen’s rugby and cricket ground, with a clause that once prohibited the playing of association football at the ground having been lifted.

The move was not without controversy, with an opinion piece in the Evening Post going so far as to question whether the decision would lead to the end of rugby football in Swansea.

The Swans would spend two seasons at St Helen’s before returning to The Vetch, with the club having to pay to improve the battered and scarred playing surface, as well as carrying out work on the North Bank.

On the field, matters were very different too, most notably when it came to the identity of those pulling on the famous white shirts.

There were those players who would lose the prime years of their careers to the war, some would never play again.

Sides were largely made up of players too young for conscription, a smattering of older players and ‘guest’ or ‘visitor’ selections.

This allowed any player handed a military posting to turn out for the club nearest to where he was based at any given time.

For example, Arsenal’s Welsh international forward Leslie Jones and Bolton winger Ernie Jones would play for the Swans in this period

Like that pair, Reg Weston, would end up continuing with the club after his naval service and would help them win promotion as skipper in 1949.

Young talents like Trevor Ford and Paul would also make their debuts during this period.

Player contracts had been effectively written off – after all, there were some 764 players involved in the war effort.

The Blitz

And any talk of football would pale into insignificance when Swansea was besieged by the German Luftwaffe for three successive nights in February 1941, which saw approximately 35,000 incendiaries and 800 high explosive bombs dropped on the town, killing 230 people.

Targeted due to its nearby docks, the bombings resulted in over 11,000 of Swansea’s buildings and homes being destroyed or damaged and the raging fires could be seen from as far as Devon.

Some of the town’s oldest buildings including the Vetch, Swansea Castle and Swansea Museum survived the worst of the damage.

But Swansea’s iconic market and Ben Evans department store were obliterated.

The people of Swansea were traumatised by the aerial bombardment but chose to unite and show resilience despite the dreaded sound of the air-raid siren providing an ominous soundtrack to life.

A number of future Swans and Wales greats stars were evacuated from Swansea; Mel Charles headed to Nantgaredig in Carmarthenshire while Cliff Jones was taken to Merthyr.

Meanwhile, many of Swansea Town’s emerging players, including Ford and Paul, were called upon to defend Britain against the Nazis, the pair initially serving as physical training instructors.

As the town recovered and rebuilding started from scratch, Swansea only managed to play 17 regional league fixtures across the 1940-41 and 1941-42 season.

The war ends, football - and the Swans - have a new beginning

Germany would surrender in May 1945, although there would be one further season of regional leagues for the 1945-46 campaign with the FA Cup making a welcome return.

But that solitary 'Victory League' season would prove a major boost for many clubs as the top two tiers were split into North and South sections, with the Swans welcoming the likes of Arsenal, Aston Villa and Tottenham to SA1 and bumper gates.

The Football League system would be reinstalled for the 1946-47 season, but the resumption would not bring good news for the Swans – who had regularly found themselves in the lower reaches of the war-time leagues - as they were relegated from the second-tier, along with Newport County.

Nevertheless, crowds flocked to The Vetch to watch their side, providing a welcome boost to the club’s coffers in the most trying of circumstances as the war had arrived in the aftermath of the recession that had crippled the global economy.

Green initially remained at the helm but, following a disagreement with the board of directors as a tough run of results followed the arrival of several acquisitions, he would resign in September of 1947, with Billy McCandless eventually being named his successor.

It was a sad end for Green who, despite being at the club for eight years and 123 days, took charge of just 48 official league fixtures.

McCandless would go on to have a long spell in charge himself, helping the Swans win the Third Division South title in 1949 with a side including players of the calibre of Roy Paul, Reg Weston and Frank Burns, successfully building on the foundations his predecessor had helped put in place.

By that point a semblance of normality had returned to life in the UK, and not just to football, but it is a period in history that will never be forgotten for the tremendous sacrifice made by so many.